Employee Compensation in the ESOP Company

SUMMARY

Employees in an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) company have more interest in their company’s compensation program than most everyone else — not just in their own compensation, but in the compensation program overall and how it impacts every other employee. A well-designed, administered, and communicated employee compensation program can make the difference between a staff that truly believes in the organization’s mission and one that is just there for the great retirement plan.

INTRODUCTION

In the typical employment situation, employees consider compensation a “management issue.” Since they are detached from information, and don’t really perceive a “stake” in the company’s success, employees tend to care more about earning more rather than what is best for the company. The “zero sum game” feeling, that any dollar that goes to someone else doesn’t go to me, pits employee against employee and employee against management — all focusing on something other than the success of the company. Add to this the media attention on gender pay gaps, executive compensation and lucrative stock payouts, and pay becomes an even greater distraction.

To reduce the impact of these concerns, ESOP companies should strive to “take compensation off the table” and out of the minds of employees. It does not mean that pay is not important – in fact, it is the opposite. What it means is that by having a competitive and equitable compensation program, pay is no longer a divisive issue. In an ESOP company, the entire workforce, from executive to entry-level staff, should feel a shared commitment to the long term strength of the company, if for no better reason than it is in everyone’s best financial self-interest. Divisive compensation issues distract from employee engagement and shared commitment, and can foil all the other efforts to keep the team on the same path.

Ultimately, the “compact” between an employee and their employer in the ESOP context is that everyone is working together for everyone’s success – regardless of the role, we all benefit if we all succeed. Of course there are higher-paying jobs, and everyone understands that, but employees in the ESOP environment have a personal stake in whether higher-paid employees are contributing value equal to their pay. A truly fair and equitable compensation plan is one that assures all employees that what is being paid is “right,” and in their best long-term interests.

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRANSPARENCY

First and foremost, the compensation program in an ESOP company must be transparent. However, transparency has its limits, because whether they work for an ESOP company or not, people remain people. They do not always want everyone else to know what they earn, and some employees will never be satisfied, and use the information that results from full transparency as more fuel for their fires. The challenge therefore is to find a balance that provides the information that is truly needed with that which will only open a can of worms. What is crucial to ensuring both fairness and the perception of fairness is that the employees know the process that is used to determine their pay. If they know that the same process is applied to everyone, they do not need to know the pay of every individual employee to know that they are paid fairly.

At a minimum, all employees of ESOP companies should be aware of their compensation potential – that is, what is the range of pay deemed appropriate for their job? They should know their position in the pay range, the reason they are in that position, and what they need to do in order to advance or earn more. In addition to this information, they should also know the mechanics of how the compensation program is designed – how jobs are assigned to pay grades, how pay ranges are determined, and the mechanism for determining an individual employee’s pay. Communication about should always be the same as communication about other company information; suspicion arises when an organization tells either less or more than they do with other data.

DESIGNING THE EQUITABLE COMPENSATION PROGRAM

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to the development, implementation and administration of a fair and equitable compensation program for any environment. There are, however, characteristics of programs that actually work and achieve the desired results.

Compensation Philosophy

Essential to a fair and equitable compensation program is the existence and communication of a Board-approved compensation philosophy. A compensation philosophy explains, in plain English, how the company intends to use compensation to attract, motivate and retain the employees it needs to achieve its mission. It is critical in the ESOP environment because the employees are the owners, and through the Board, are responsible for determining and maintaining that philosophy. For the prospective employee, understanding the philosophy provides context for the entire employment relationship, explaining what they can expect.

Because much of the long-term value of the total compensation package of an employee in an ESOP company comes from their ownership stake, the compensation philosophy must clearly set forth the standard that can be a test for all compensation initiatives and programs.

A typical for-profit company might have a pay philosophy like this:

“The philosophy of XYZ Corporation is to ensure that it provides compensation opportunities that will allow it to attract, retain and motivate the employees it needs to be profitable, and will therefore target compensation at the middle of our competitive market.”

On the other hand, an ESOP company whose focus is on building long-term wealth for its employee-owners might take a position like this:

“In order to be successful and build long-term wealth for our owner-employees, ESOP Company will provide competitive cash compensation while recognizing that the ultimate recognition for employees’ contribution is the long-term profitability of the Company.”

The difference in the message between the two philosophies is more than semantic. In the first example, a company’s ownership uses pay as a method of building wealth for its owners; it will pay that which it needs for the company’s success, and thus the owners success. The company is concerned with its ability to attract the type of people it needs “today” and is focused on itself, rather than its employees. On the other hand, the second clearly states that the objective is building wealth over the long-term for all owner-employees. Decisions on compensation will be made in such a way as to pay what is needed to grow value – the priority is less on today, and more on tomorrow.

It may appear that the “ESOP Company” philosophy suggests that its employees would be paid less, because the company’s resources are being focused on the future. However, properly thought-through, the opposite can in fact be the case, because it is only in the “zero sum gain” mindset that a pool of financial resources is considered fixed. Paying above the competitive market, for example, might result in less than glowing short-term results, but would allow the company to hire more qualified and motivated employees, thus building greater long-term value and return to the employees.

Program Design

Compensation needs to be fair, and just as importantly, to be seen as fair. Every employee in an ESOP company should be focused on building an organization that will have long-term value – it’s in their best interest. If the philosophy is clear, the job expectations laid out, and the process for development and recognition are clearly laid out, fairness is an easy outcome.

A fair and equitable compensation program in any organization requires three major components:

- Valuing jobs to the organization;

- Accounting for the competitive market;

- Measuring the relative contribution of employees toward their job expectations.

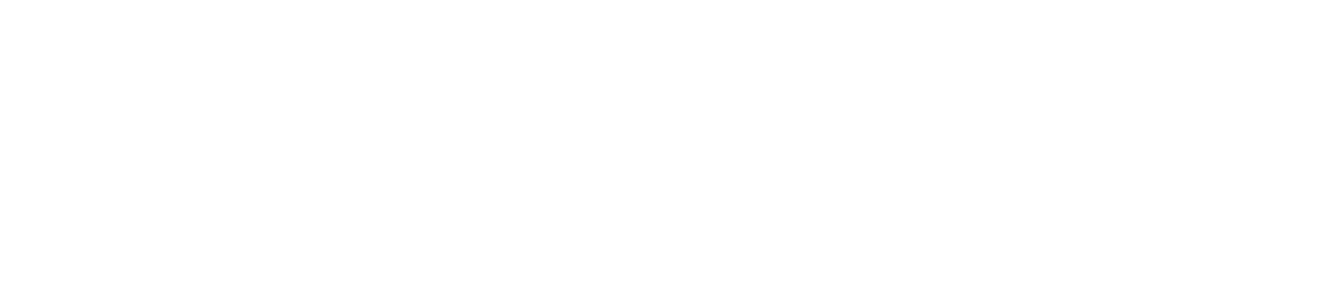

Internal Equity – The Contribution of Jobs

Every job has a value to the organization – otherwise the job would not exist. But some jobs are able to contribute more, because they require more skill, control more resources, or place the organization at risk. Jobs that can impact the organization to a greater extent (either positively or negatively) are frankly more important – and people understand that people in those jobs should be paid more. Employees know this intrinsically, but cannot always put it into words. Management frequently fails by not communicating why the pay opportunities for some jobs are greater than for others.

It is easy within a department to see how relative contribution analysis works. Accountants are paid more than accounting clerks because their work is more complex and requires more knowledge; a Controller is paid more than an accountant because of a higher level of responsibility; a CFO is paid even more because someone in that job brings together accounting and financial analysis at a very high level and is critical for organizational success. The question is how this comparison can be made across departments Are engineers and accountants “worth” the same? What about accounting managers and computer network managers, or lawyers and doctors? It is difficult to just hold one of each in your hands to see which weighs more!

It may seem like a difficult task, but it is really quite simple. For decades, management has had several tools useful in determining internal equity – they all fall under the broader term “job evaluation.” A job evaluation process or program breaks down the characteristics of jobs (e.g., knowledge and skills, problem solving) in an objective manner, allowing for comparisons of jobs not to be made against each other, but against an objective standard. Weighting the various characteristics and assigning points to ever increasing levels of each characteristic allows for calculation of a score – jobs with similar scores are perceived to have similar value, and thus have similar compensation opportunities (assigned to the same “pay grade”).

This type of approach further:

- Allows for specific explanations about why one job is valued more or less than another;

- Provides a rationale for why people in a job should be paid more or less than that in the competitive market; and

- Gives the organization a method for determining the value of a job when it is unique, a combination of multiple roles, or simply can’t be found in a compensation survey.

Employees should be told about the mechanics of the plan – how it works, what characteristics are considered, and how changes to jobs influence changes to pay grade assignment. While some employers go further and publish their entire pay structure – all the grades and all the jobs assigned to them – this is not necessary. Publishing the actual job evaluation measures and scores is not advisable; without the context of understanding the program itself and how all jobs are evaluated, this will cause more issues than it will solve.

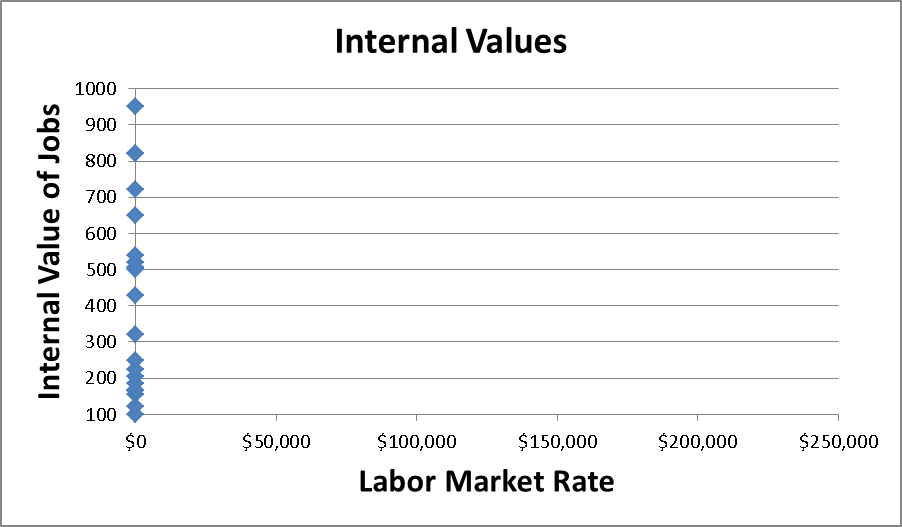

The Labor Market – Being Competitive

Competitiveness is essential. The competitive position any organization takes must be consistent with its mission/objectives, and expressed in its compensation philosophy. There are many sources of data available, with strengths and weaknesses. Whatever data source is selected, the data used must be consistent with the compensation philosophy:

- The most typical position to take is the median, or middle, of the market. Half of the employers will pay more, half will pay less. The employer will inevitably lose some employees to better opportunities, but on the other hand will be more attractive to about half of the potential employees.

- Positioning higher in the market (usually expressed as a percentile or a percent above the median), gives the company the opportunity to attract more potential employees, and reduce the risk of loss simply due to competition. While it gives the opportunity to attract and retain more qualified and dedicated employees – it does not guarantee it. Simply paying more does not change behavior; if the employer wants to pay more, they should also expect more.

- Positioning below the market is not recommended, for obvious reasons. Many non-profits fall into this trap, thinking that they are obliged to be cheap. Similarly, short-sighted employers interested in keeping costs down to generate higher profits may take this approach. In the long-run, having less qualified, disengaged employees will not achieve a mission or build profits.

It is common for organizations to look at data for companies they consider to be competitive, or those who are most like them. In truth, the “market” should be seen as composed of those employers who are likely candidates to recruit the company’s employees, or would be seen as a good training ground for candidates for employment. Each job has a different market, based on three general characteristics:

- The relevant geographic area – How far will people commute, and how likely are you to relocate people for the job.

- Industry expertise – Does the job require expertise in a particular industry? If not, realize that any employer of that skill set, or comparable skill sets, is a competitor.

- Organization size – Size is always a good predictor of pay, because it is indicative of resources, as well as the complexity of work – the job of a “controller” at a Fortune 500 company is far more complex than a similar job title at a local tool and die shop.

ESOP management may wonder whether it is important to compare their wages and salaries with other ESOP companies. While it does make sense in some sense – it is unlikely that there will be a sufficient sample of ESOP companies in a given industry in a relevant location. While it is certainly interesting data, it probably isn’t particularly relevant.

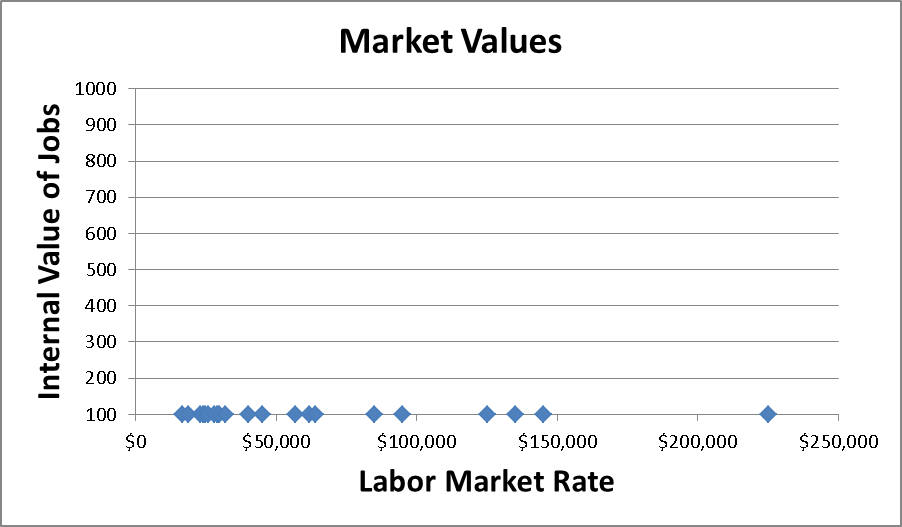

It is obvious that each one of these two crucial components is one dimensional. Both need to be reconciled if a company is to have a compensation program that is both internally and externally equitable. Market data and the results of internal equity studies come together in the formation of pay structures, which are simply competitive ranges of pay assigned to each pay grade.

Companies that only use labor market data often run into the problem of what to do when market rates for jobs increase at different rates – which they always do! The solution is not to take averages, which wash out the impact of the changes, but to use all of the data in an equation such as the one depicted above.

Measuring Contribution – Paying Appropriately

Performance management is everyone’s problem in an ESOP company. In a “conventional” organization, developing, appraising and disciplining employees is again seen as a “management problem.” While employees may resent their non-performing colleagues, they don’t feel they have a stake in the problem, except to the extent that they complain about how non-contributors makes their lives harder. While it is still management’s responsibility in the ESOP company, employees actually have a stake in the result. An employee wasting resources is affecting the bottom line of every employee, and their future. Employees will have less tolerance for those that have not bought in, a problem that should become more noticeable the higher we climb on the organization chart.

What makes an employee’s contribution valuable in an ESOP company? The same thing that should be top of the list in any organization – how they do their job. Employees’ contribution needs to be assessed based on the job they are supposed to perform, not abstract concepts of “getting along,” or “competencies,” or any of the other “performance appraisal of the moment” techniques. Performance management continues to be the biggest “pop HR” topic in management, and most new innovations should be avoided.

If an organization wants to measure an employee’s contribution fairly and equitably, as it should be, the company need only take out a copy of the job description and write in the margin how each duty is performed, and the results of each responsibility. When an employee is doing everything the right way, we should be more than satisfied. When an employee isn’t, this method points a finger directly at the things that need improvement, and the employer and manager need to make a plan to bring contribution to the level it should be. Focusing on development and the job takes away bias or the influence of factors other than the performance itself.

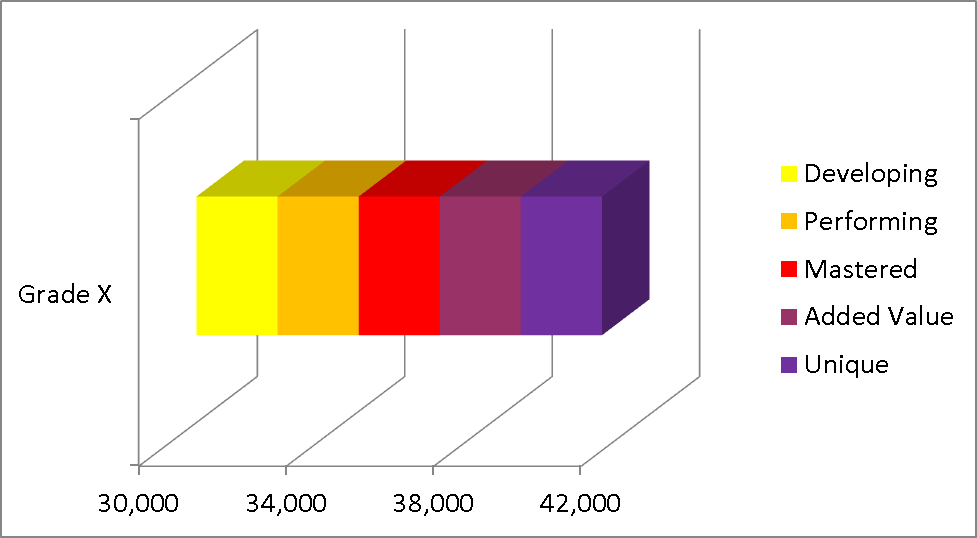

In a properly designed program, compensation will easily reflect different levels of contribution. The range immediately above is split up into five parts, reflecting differing overall levels of performance. The center of the range, the level defined as “mastered,” is appropriate for an employee who is performing the job the way it is expected. This part of the range was illustrated earlier as the line that reconciles internal and external value.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

In a properly structured program, a company has:

- Developed a compensation philosophy based on its mission, the interests of its stakeholders (including owner employees), its strategic plans and its business model.

- Measured and valued each job, creating a pay grade structure.

- Applied the compensation philosophy to the pay grade structure, collecting relevant labor market data and creating ranges for each pay grade

- Assessed the performance and contribution of each employee against the expectations of the job as put forth in the job description.

Now it is possible to determine appropriate pay for each employee, and all the tools are in place, ready to make a fair and equitable decision. With whatever method feels most comfortable, ESOP companies should seek to ensure that every employee is paid in the right part of the appropriate range. For example, in the illustration above, an employee in a job in pay grade “x” who is fully performing job duties, should be paid between in the red segment (“mastery”) of the range. Some organizations prefer to have that flexibility to address individual performance or send messages about efforts. Others may want to reduce the possibility of bias and have a specific score generate a specific range position.

The most significant difference in this approach to compensation management, and what makes it essential in an ESOP environment, is that it focuses on the current “price tag” for each employee based on their contribution – not linking to what kind of increase one should get. The truth is, the percentage amount of increase an employee should receive is irrelevant – what is relevant is what the resulting compensation matches the employee’s contribution. The failure of most compensation programs can be illustrated in the following graphic:

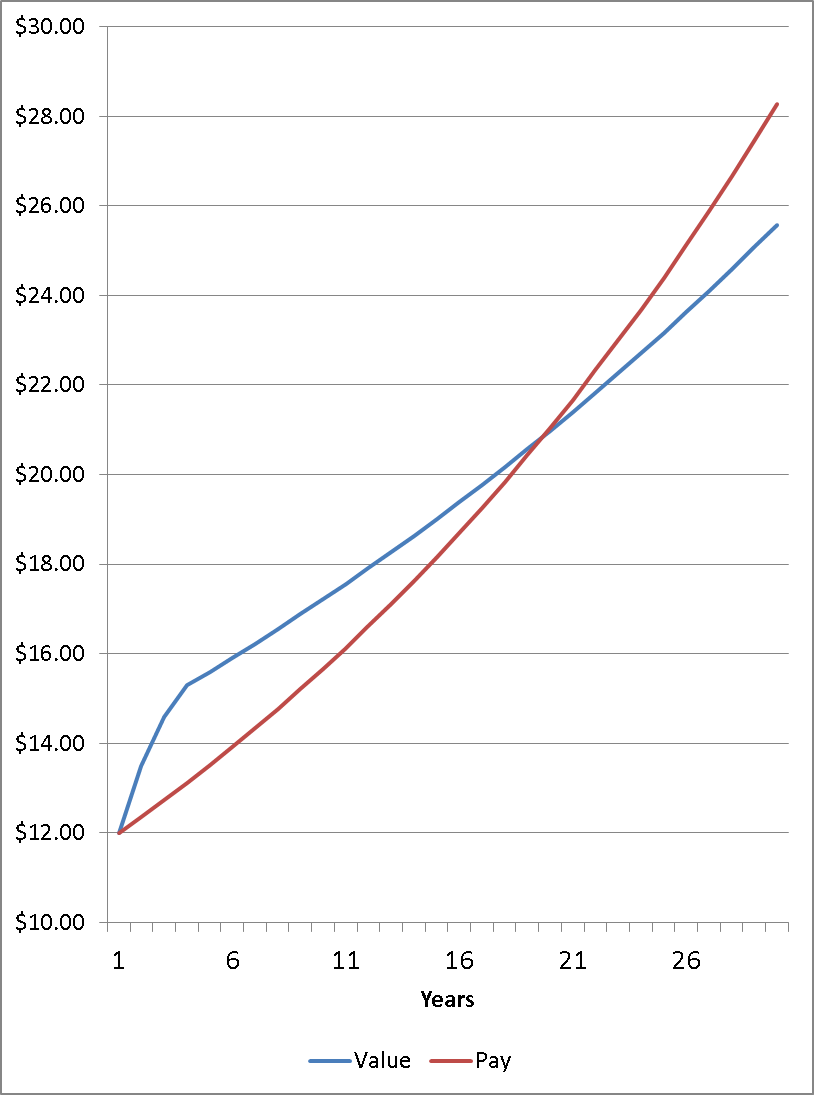

The blue line represents both the growth of the employee and their value in the market. Value increases rapidly in the first few years as employees learn and master the job. While there can be incremental gains in contribution once the job has been mastered, most of the increase in value is based on increases in the market value for the job (assumed to be an average of 2.5% over time). The red line represents the typical compensation program. In this illustration, a three percent (3.0%) average increase is assumed, reflective of historical practices in most industries. As is obvious from the exhibit, value and pay are only aligned twice – once at the hiring date and then again approximately 20 years later. Perhaps ironically, over the course of a thirty year career, the cost of paying “correctly” is almost exactly the same as the cost of paying using an ineffective methodology.

Whenever the red line compensation is below the blue line value, there are more opportunities for the employee to leave for higher levels of compensation. Particularly for entry level jobs, the gap between value and actual pay can leave employees’ pay well below the 25th percentile of the market – it should not be surprising to see employees leave when they have the opportunity to do the same work and be paid fairly. A more appropriate way of managing pay is shown in the following exhibit, which tracks the pace of employee pay adjustments over five years in three scenarios:

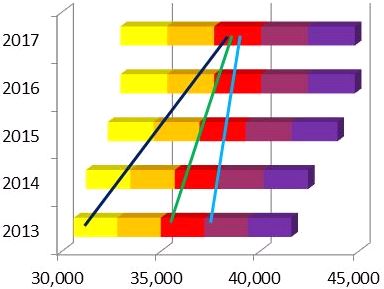

As the market values of jobs change, pay ranges will be adjusted. Managing compensation over time is a function of both changes in the market and improvements in contribution. If, as an ESOP company should, we strive for fairness and equity, there must be a mechanism to ensure that pay is at the right level at the right time. A new and inexperienced employee, represented by the navy line, will need to move much farther across the chart to be paid competitively – accordingly, there will be large percentage increases early in a career, to help bridge the gap. Once the alignment between pay and contribution is achieved, pay growth steadies, in a way very similar to that of the employee who has already achieved mastery, represented by the green line. This employee will expect to receive increases as the market changes, but not so much that pay becomes more than competitive. Finally, the light blue line represents an employee who may have had to be brought in above the market, or one who initially appears more qualified. Increases are given, in accordance with contribution, as appropriate.

CONCLUSION

Matching pay and value is critical to success. An approach like this should be taken by every employer, for the good of its business. For the ESOP company, however, it is essential — it means that every employee is paid according to the same process, whether they are on a shop floor or in the “C-Suite.” Fairness and equity truly takes pay off the table, and focuses everyone in the company on the mission.