The Decline and Fall of “Pay for Performance”

Congratulations on your new hire. “Ron” looks to be a promising new employee. He came to you with a strong resume and enough relevant experience to suggest that he is the kind of employee you see as a long-term, steady provider. For his part, Ron hopes to enjoy his work, feel acknowledged, and be compensated in line with the value he brings to the company and his growing value in the external marketplace. Compensation isn’t the most important thing for Ron, but his emotional response to his compensation can set the tone on how we sees the organization as a whole. He needs to know his contribution will be rewarded and be consistent with his performance, that of his colleagues performing at the same or different levels, and fair market value paid by other employers who could use Ron’s knowledge and skills in very similar jobs.

Your human resources director explains to Ron your “merit pay” plan. It’s pretty standard, part of the overall compensation strategy that is based pretty much on what this year’s budget will allow. She’d like to be able to promise a merit increase of 3% each year as long as performance meets expectations, both budget and performance review allow, a percent or two more. Ron nods knowingly; this is standard and reasonable. It’s pretty much a run-of-the-mill pay-for-performance plan, but he has every intention of far exceeding expectations and getting a 5 or maybe even 6 or 7 percent increase each year.

What neither Ron nor the human resources director (or, for that matter, the accounting executives or even the CEO, in all likelihood) understands is that this compensation plan is already doomed to failure. Why? Because it will never allow Ron’s actual pay to match either his true value to the company at any given moment, or his value in the competitive marketplace. In other words, if Ron is the steady developing, long-term great guy we think he is, this plan will ensure he is underpaid for about 20 years. If he turns out to be star, his value to the company will quickly outstrip his compensation, even at his dream 7% a year, making him a perfect target for a competitor who will greatly appreciate the professional development you’ve provided Ron over his first 12-24 months on the job. If Ron is the resilient team player who hangs in there anyway, for some of the myriad reasons people do even when they see your competitor paying their friends at a much more attractive level, eventually the reverse will be true: Ron’s compensation will continue to rise even when his value to the company does not.

Whether you lose Ron in the short term and have to absorb the painful cost of replacing him and starting over, or you keep Ron – and always keep him at a compensation level out of sync with his current performance value – your company’s “merit pay structure” or “pay-for-performance plan” will not successfully differentiate between levels of individual performance, let alone drive higher levels of performance. Your compensation structure will not succeed at keeping Ron and his peers engaged and productive, nor will it keep away the competitors slinking around your front gate. Your plan’s design will not allow you to achieve your objective.

The Need for a Philosophy and a Program that will Actually Work

A compensation plan that works will deliver compensation that accurately reflects employees’ contributions and individual value to you, the employer. Almost all standard pay-for-performance plans, laudable in their intentions, fail to do this. In a recent Willis Towers Watson study (https://www.willistowerswatson.com/en/insights/2016/02/pay-for-performance-time-to-challenge-conventional-thinking), participants reported that only one in five merit plans drives higher levels of performance, and fewer than one-third successfully differentiate between levels of individual performance. This should come as no surprise, as plainly and simply, the math doesn’t work.

Of course employees who are better performers should be paid more – so that pay is fair and equitable, and so productive employees continue to perform at high levels, experience job satisfaction, and commit to the company for the long term. Unfortunately, the tools used to achieve this objective are fundamentally flawed, because they do not ensure that employees are paid for the long-term value of their performance. Merit pay plans are by their very nature retrospective, providing employees increases based on their contributions in the past. If these plans actually delivered increases over time that would ensure that employees were paid for the actual current value of their contributions, they could potentially work. However, both design parameters and historical practices show that they do not do accomplish this.

Very likely the abject failure of current approaches to valuing performance will lead to discouragement and return employers to even more dysfunctional approaches to pay. What is needed, instead, is a simple pay calculation method that ensures that each employee is paid, continuously, commensurate with the value of his or her services.

Most compensation plans have two components: “program design,” which determines the compensation opportunities available to employees in a job, and “program administration,” which determines the individual pay of employees. While program design is far from universally effective across any industry, program administration can fail even the best of designs. Let us focus today on program administration.

What Should a Pay-for-Performance Plan Achieve?

A pay-for-performance plan should ensure that employees are paid fairly and equitably, consistent with the value of their contribution to their employers. The plan should provide adjustments that bring pay from its starting point at the date of hire to wherever it ought to be, at the appropriate pace, and then maintain it at a level that reflects both on-going performance and changes in the labor market.

Such a plan must also make “good business sense.” Just as it should bring pay to appropriate levels at the appropriate time, it should also maintain pay at levels that are reasonable for the value of the work being performed. Maintaining a reasonable maximum limit on the pay for every job will help keep resources available to pay every employee fairly. Properly administered, the plan should never reach a level in which increases are not possible.

Measurement of employee value or contribution, by the way, as part of a sound pay-for-performance plan, or any compensation program for that matter, should never include employee characteristics not relevant to the work being performed. Obviously an employer may not discriminate against “protected classes,” but the employer should also be free of bias for or against people with any non-work-related characteristic, legally protected or not. Further, individual’s personal circumstances (e.g., number of children in college, spousal income, outside distractions from family emergencies) should never be considered in setting pay. While doing so may appear on the surface to be “compassionate,” it is completely inappropriate in a professional business setting and will not contribute positively in the long term.

Why Merit Pay Plan Designs Fail

A true pay-for-performance compensation system would focus on delivering increases consistent with each employee’s performance. Unfortunately, merit pay plans are, by and large, not designed to do this. Their design instead distributes the annual budget’s increase for compensation with no relevance to performance, but based on either whatever increase the employer believes it can afford for the next year, or on surveys that describe the increased compensation budgets of other employers.

Typically, the budgeting process for merit increases makes little actual business sense. Using the resources of the organization as an input into the employee compensation budget seems logical, but it has no relationship to employee performance. The practices of other organizations, moreover, are entirely irrelevant to the performance of your organization’s employees. Such surveys completely fail to recognize the demographics of your particular workforce. An organization with well-paid, seasoned employees, for example, needs a much smaller “budget” to maintain performance-based compensation than one with a workforce heavily populated with less experienced employees who are still growing into their jobs. If a budget process is used, it should relate specifically to the needs of the organization and the performance of its employees in the fulfillment of those needs.

At best, merit increase programs will achieve a more equitable distribution of increases in any given year. Management simply hopes that the percentage increases high-performing employees receive will dwarf the increases received by low-performing employees so the high performers will feel “rewarded,” and thus be motivated to continue to perform at that level. The problem, of course, is that this works only if higher performing employees are being paid more than their lower performing counterparts before any increases are given. There is little solace to be gained by a high performer who realizes that, despite this most recent increase, she is still being paid less than a low performer.

To compound the problem, management typically has a psychological need to ensure that all employees get increases every year, limiting funds available to actually reward performance. This desire is not entirely unfounded. It is reasonable to worry that employees who do not receive increases each year will become disgruntled and either leave or functionally disengage. Management often feels that employees, particularly those who perform at or above expectations, should receive increases either to keep up with changes in the market or to protect employee purchasing power as the cost of living rises. As a result, most of the budgets for merit pay programs do not go to rewarding performance, but are spent on providing “across the board” increases.

Once an across the board increase is given… well… across the board, the compensation budget has little left for “pay for performance.” The labor market increases at a historical rate of between two and three percent per year, and the cost of living (as measured by the Consumer Price Index) increases at a similar rate. Merit budgets, as reported by many studies every year, range in most years from 2.5-3.5 percent, and in very good years reach as high as four percent. If three percent of a budget is dedicated to providing everyone a three percent increase, there is just not enough money left over to actually reward “performance.”

The Willis Towers Watson study commentary notes that 99% of employers feel compelled to give increases on an annual basis.* Why? Because that is what we do, apparently. Is there really a reason to give an increase every year? Alternatively, is an increase every twelve months possibly too infrequent to effectively reward changes in performance? They call for a paradigm shift – a reasonable response.

So let’s shift our paradigm right now by acknowledging the myths behind the design and administration of supposed pay-for-performance compensation models. Let’s face the facts.

Merit Increases don’t drive performance.

The research shows it. They don’t, nor should they. For a full explanation of this phenomenon, read Drive by Daniel Pink to understand the failure of money to motivate. A merit increase at best acknowledges an employee’s performance over the past year, with no guarantee that a similar reward will be forthcoming in the following year. Why should employees feel “rewarded” or “motivated” because an employer is paying them what they should be paid? The truth is that the best thing a merit pay program can do is to neutralize feelings about compensation. On the other hand, such a program has a high potential for arousing negative emotions in employees.

Because each “year” stands on its own, there is no guarantee that full value, or even full equity, will ever be achieved through a series of individual adjustments. Just as importantly, if the “reward” for high performance is a large increase every year, the expectation will be that the employee is recognized for high performance only by high increases – setting an unrealistic expectation, because ultimately an employee can be paid only so much for providing a particular service. The focus on the amount of the increase, rather than the amount paid, is philosophically problematic.

No matter how difficult for management to accept, people do not behave logically when it comes to compensation. The “rational economic man” is predicated on a belief that people will always act in their own economic self-interest – and they patently do not. Many managers have encountered the “insulted” employee who rejects a one-percent increase because it is so low. Such behavior seems inconceivable, but, when it comes to compensation, people are irrational. Expecting people to be excited about a one percent increase because other employees are getting nothing is simply delusional.

Performance appraisal programs are ineffective because they do not focus on the job.

Performance appraisal is rightfully considered a tedious, stressful and ultimately meaningless process, dreaded by managers and employees alike. Generic performance appraisal forms downloaded from the Internet, or highly complex competency or attribute-based appraisals that focus on abstract characteristics such as “exhibiting dedication,” are difficult to understand or apply to individual employees. Rating systems based on “meeting expectations” cannot even pass the basic test of whose expectations are to be considered.

If the typical performance appraisal process had any real meaning or value, it would not be the one management process that is almost always completed far behind schedule, if at all. It’s a process most managers complete only because they are required to – and frequently do it only when “completing performance appraisals” is one of their own performance measures.

Why is the process so dreaded? Because it effectively comes down to whether an employee is a “good” or “bad” person. Performance appraisal programs do not encourage honest dialogue with good employees, because any formal discussion of areas for improvement risks a reduction to their “score” and thus potentially their pay increase. Once-a-year discussions with poor performers do little to improve performance. Such issues need to be dealt with on a daily basis, not saved up for a long and tense discussion that will lead to little more than “we’ll have the same conversation next year.”

Employees become associated with, and identify with, their performance rating.

It is actually common for employees to refer to themselves by their performance rating: “I’m a 4!” “I’m outstanding.” The reality is that one can be outstanding and still have areas to improve upon, particularly for those new in a job. If expectations are low, one can easily “exceed expectations,” but does that make the employee “outstanding”? Performance appraisal terminology is crude and simplistic and difficult to use in a real performance management process.

What happens when a “4” employee learns that he will not receive another 5% increase – because he’s already paid 25% more than his value to the organization? Employers who define people by their average annual performance rating, rather than their ongoing value to the organization, actually “train” employees to be demanding and petulant.

The math doesn’t work

All philosophical considerations aside, the fact is that the math in the typical merit increase program doesn’t work. For context, let’s return to “Ron,” your promising new hire who opened our story. Let’s assume that the objective of pay for performance is to ensure that Ron will be paid consistent with the value of his services to you, his employer. This means that the plan should ensure that Ron receives increases sufficient to move him from whatever he’s paid at his date of hire to a market-competitive position at the time his performance is “market-competitive.” For this example, assume the following:

- Your company maintains a 40% wide pay range for the job Ron will hold, which has a midpoint of $40,000/year, meaning that Ron, hired at the range minimum of $33,300, will need to receive increases of 20% (assuming no change to the range) to reach the market-competitive target.

- The labor market for Ron’s job is moving at the rate of 2.5% per year.

- Had Ron been hired with the minimum qualifications for the job (at the range minimum), it would take him three years, assuming normal development, to become a full contributor, performing all job duties at the level expected by your organization.

At the beginning of year four, the midpoint of the range will be $43,100, which means that in three increases, if Ron turns out to be a typical “meets expectations” employee, he will need to move from $33,300 at hire to $43,100 when fully performing the job, an increase of $9,800 or a total of 29.4%. To achieve the objective of a pay-for-performance plan, accounting for the effects of compounding, Ron will need to receive an average increase of 9% per year.

Most simple merit increase plans are based on a distribution of available funds for increases, and they vary considerably in sophistication. Assuming a three percent merit budget (a reasonable consensus of the multiple surveys projecting employer plans for 2016), a very simple merit increase model might look like this:

| Performance | Increase |

| Far Exceeds Expectations | 7% |

| Exceeds Expectations | 5% |

| Meets Expectations | 3% |

| Below Expectations | 1% |

| Far Below Expectations | 0% |

This simple table meets the objective of providing larger increases for higher levels of performance. If our new hire, Ron, is on a normal development track, obviously this plan will not meet Ron’s pay-for-performance objective. The 3% increase, over the course of three years, will bring him to $36,400, only 84% percent of the midpoint “target” of $43,100. To fully understand the implication of these particular merit guidelines, consider that if the “target” is set at the median of the labor market, a salary of $36,400 would likely be below the 25th percentile of the market – that is, 75% of the employees in the market will be earning more than your now fully functioning employee.

Over the long term, the problems with this program become even more significant, because, with no consideration of current pay when determining increases, the same rule applies essentially every year. If we assume performance is constant, and that the guidelines stay in place, in ten years we would see that, as a “meets expectations” employee, Ron would still not have reached the market competitive position he should have reached after three years. In fact, this employee will not reach “competitive” pay during his entire career, even after thirty years.

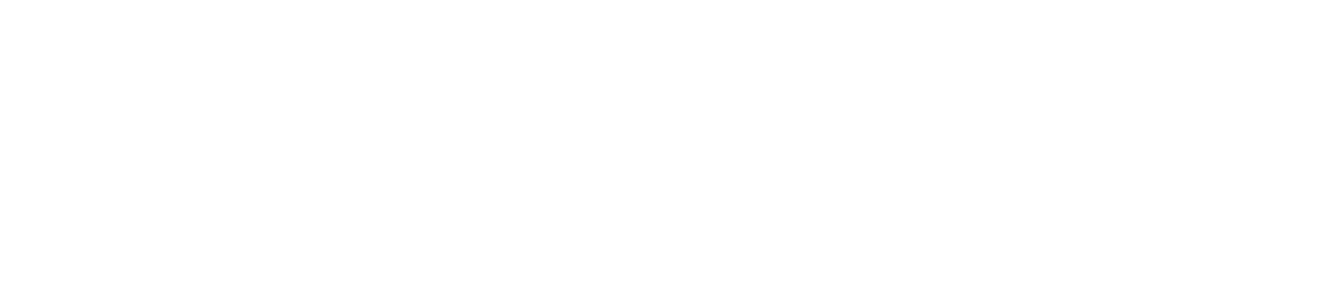

Let’s look at this visually, over the course of 30 years or so:

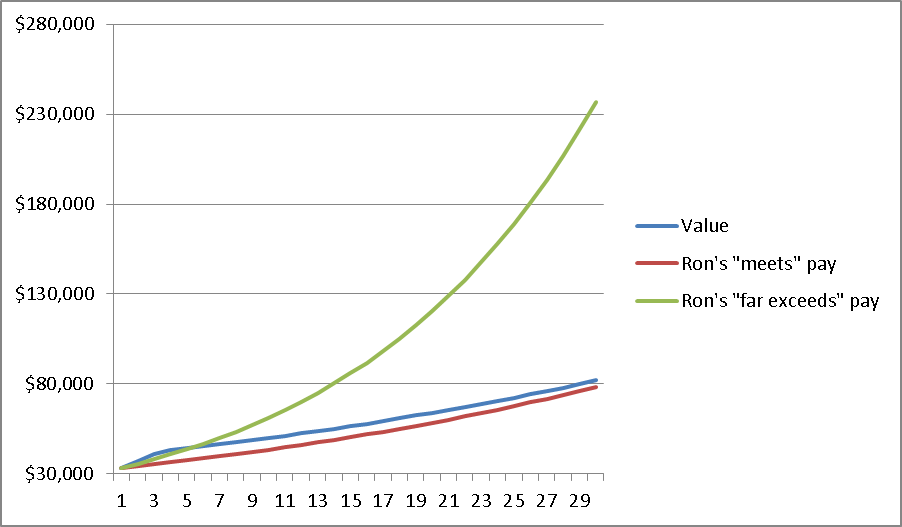

Ron will never be paid his value, and if we don’t believe that it will affect his attitude, we are deluding ourselves. Knowing that this plan fails for the employee with typical development, what if Ron truly performs as a “star”? To grossly oversimplify things, consider that an employee “exceeding expectations” would learn the job in two years rather than three, and the “far exceeding expectations employee” would learn it in only one:

- If Ron “exceeds expectations,” he would be earning $36,700 two years into his new career with you, 87.4 % of the target of $42,000 appropriate pay.

- Should Ron actually “far exceed expectations,” which he aspired to do upon hire, he would be at $35,600 when he becomes a full performer in the job, 91.3% of the target.

In either scenario, Ron is in a slightly better position against his target, but paradoxically in a worse position against his value in the market. Higher-level performance employees would expect to have higher values in the market than the “median” (which represents typical development). If Ron really is a “far exceeds expectations” employee, he now probably has at least the 75th percentile value in the market, making his pay even farther below what is appropriate for his compensation – likely less than 80% of his true value.

Should he really become a “far exceeds expectations” employee, the situation is now even more problematic. Having established the entitlement to a seven percent raise, Ron will have become competitive after five years, and will be “competitive” at the 75th percentile after only seven years. However, with no check on increases, at ten years you will now be paying Ron more than 28% above the market, and then, at 30 years, the chart tells all.

It is fair to point out that many merit pay plans are more sophisticated than the simple one described above. The next step in a pay-for-performance plan design is to account for current pay – this is intended to get employees to the target more quickly while keeping pay from growing out of control. A “merit matrix” using the three percent guideline for keeping a “meets expectations” employee competitive might look like this:

| Performance | First Quartile | Second Quartile | Third Quartile | Fourth Quartile |

| Far Exceeds Expectations | 9.0% | 7.0% | 5.0% | 3.0% |

| Exceeds Expectations | 7.0% | 5.0% | 3.5% | 2.0% |

| Meets Expectations | 5.0% | 3.0% | 2.0% | 1.0% |

| Below Expectations | 3.0% | 2.0% | 1.0% | 0.0% |

| Far Below Expectations | 1.0% | 1.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

This table is better to the extent that it recognizes that employees paid farther below the target/midpoint need to be paid more in order to get them to their target faster. However, despite a design that considers range position, this matrix will not get an employee to the appropriate range position much faster than the simple guide chart:

- The “meets expectations” employee in this model will still not reach the range midpoint at any time in the foreseeable future. In fact, in this example, a “meets expectations” employee will never be paid median market value.

- It takes five years for the “far exceeds expectations” employee to reach only the median of the market. Imagine Ron, fully performing the job for four years: He does not reach even the market value before he leaves for another employer whose compensation plan demonstrates acknowledgement of Ron’s value.

Is the “merit matrix” without hope? Absolutely not. It is certainly possible to design a merit increase matrix that will work and achieve the objectives of pay for performance. It would probably look something like this:

| Performance | First Quartile | Second Quartile | Third Quartile | Fourth Quartile |

| Far Exceeds Expectations | 24.0% | 12.0% | 5.0% | 3.0% |

| Exceeds Expectations | 18.0% | 10.0% | 4.0% | 2.0% |

| Meets Expectations | 12.0% | 8.0% | 3.0% | 1.0% |

| Below Expectations | 3.0% | 2.0% | 1.0% | 0.0% |

| Far Below Expectations | 1.0% | 1.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

In a model like this, employees at all levels of performance reach the target (midpoint) at a point in time reasonably in line with their development, and pay is kept in line so it does not exceed the value of the employee’s services to the employer. However, this merit matrix is never seen in practical use, probably for the following reasons:

- Management cannot tolerate the idea of a 12% increase for “meets expectations” performance, let alone an 18% or 24% increase at all. Because the focus is placed not on the value of the employee’s performance but on an abstract percentage increase that seems “outlandish,” a merit matrix like this will never be accepted.

- Employers cannot communicate why “far exceeds expectations” is worth 24% sometimes, and 3% at other times. Again, the problem is that the employee has become one who “far exceeds expectations,” a definition that entitles that person to some type of reward. A 3% increase for “far exceeds expectations” performance is perceived as insulting and cannot be reconciled with a “meets expectations” employee who receives 12%. While that position might be perfectly logical from a mathematical standpoint, the fixation on the percentage increase, rather than the actual pay, blocks rational reactions.

- Employers do not perceive that they can afford this matrix. Given the way that most organizations budget for compensation, using their current payroll as a base and deciding what they can “afford,” the amount needed to provide competitive increases is cost prohibitive. Assuming a normal distribution of both performance and pay, the cost of this sample budget is more than eight percent of pay.

So How does one Budget for People?

Merit-increase plans fail because they are tied to a flawed method of budgeting for people. In nearly every budget item other than human resources, the budget process begins by determining the costs of the desired product or service. To budget for steel, for example, a manufacturer determines the amount of steel needed to produce its desired number of products, then contacts suppliers to determine the price it will have to pay to buy that amount of steel at a desired level of quality, and sets the budget accordingly. Of course negotiations over price and quality might be necessary, and changes to products or manufacturing processes might occur, but ultimately the amount the company will need to pay is based on how much it will purchase, and at what price.

For some reason, the budgeting process for the cost of “people resources” does not begin by determining the cost of the resources. As noted earlier, it consists of looking at the current amount, and determining how much it can afford to increase the total, and then distributes it according to its desired methodology. At no point does this process examine the actual cost as if the services were being purchased every year. The process relies on the assumption that employees will continue to work for compensation levels less than they can receive in the market. Management has reason to believe this will work: Experience has shown that they usually can keep people despite paying them below their value.

The flaw in the management theory of “captive control” is that it assumes that employees will continue to produce at the same level of value to the company once they realize they are not valued. The resulting dissatisfaction, disengagement and turnover of the undervalued workforce then fails to be recognized as a “real cost.” If it were, management would presumably correct the situation. However, these costs are seemingly not visible and thus not considered. As a result, management is blissfully unaware that far more money is actually lost (or not ever even earned) than the money they believe they are saving.

What if we were to apply this management method of budgeting for people to the purchase of office supplies? Imagine entering the office supply store on the first day of the new fiscal year and offering to pay 3% more than the price of a case of paper over yesterday’s price. You will simply pay the price this retailer charges, or find a different supplier or settle for a different type of paper.

You Need not Give up Hope

Rather than the ineffective and convoluted budgeting and “merit pay” methodologies that don’t actually “pay for performance,” and instead result in turnover, disengagement and poor organizational performance, consider:

- Budgeting each year based on the value of each job to the employer, multiplied by the number of employees in each job.

- Setting individual pay rates based on the value of each employee’s performance, using the “value” as a target for 100% performance.

If all of the employees are not fully performing the job and, therefore, the full budget for increases is unused, the balance becomes profit, or available for investment, or available to pay employees performing beyond the target level. Every year, simply recreate the budget using the same method. You will always have enough to attract and retain the staff your organization needs, and the organization will perform as it should, with a fully engaged workforce. It can be done.